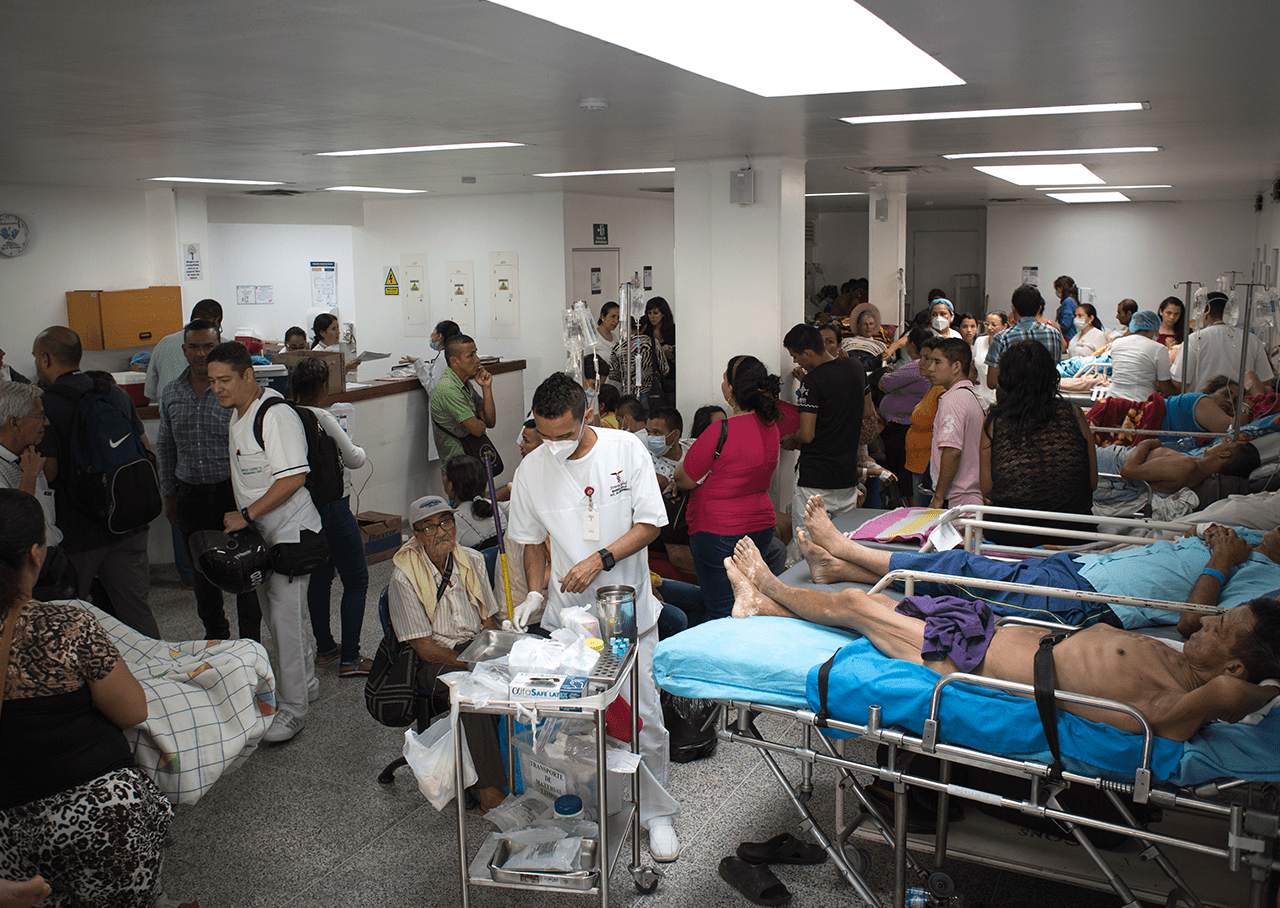

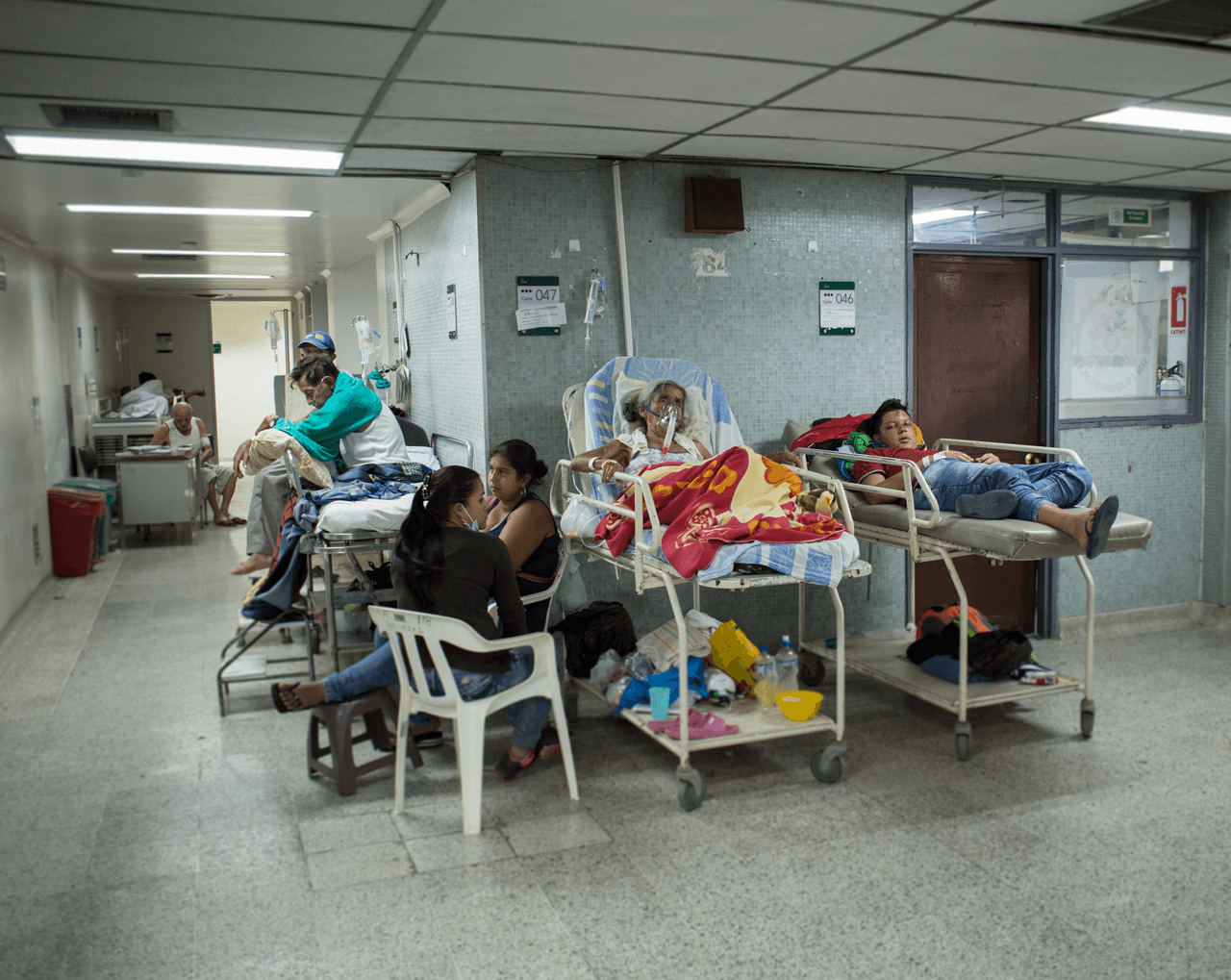

Views of the Emergency Room of the Erasmo Meoz Hospital in Cucuta, Colombia. This is the hospital that has served the most Venezuelans going to Colombia throughout 2017.

In response to the increase in Venezuelan migrants and refugees requesting emergency health services, the Colombian government issued Resolution 1449 (2017) assigning additional budget to departments along the border – Arauca, Boyaca, Cesar, Guainía, Guajira, Norte de Santander and Vichada1. It also issued Decree 866 (2017) to allow additional resources to be allocated for the emergency treatment in the public health sector of foreign nationals from a border country who are unable to pay2. It also issued several circulars dealing with the registration of and health care services for foreign nationals3.

However, the amount allocated has been insufficient. Of the COP4,000 million (US$1,350,000) guaranteed by Resolution 1449 (2017), the department of Guajira received a total of COP1,066 million (US$360,000) in September 2017. The amount spent just by the Nuevo San José de Maicao Hospital (in la Guajira) up to December 2017 was more than COP2,870 million (US$973,000), more than double the amount allocated for the entire department of la Guajira. But more worrying still is that by late February 2017 the Nuevo San José de Maicao Hospital had still not received any funds to help cover the large amounts spent treating the migrant and refugee population4.

In Norte de Santander of approximately COP11,000 billion spent on patient care in the last year (around US$3,727,000), the government allocated, in the same Resolution, a total of COP2,400 million (US$810,000) to alleviate the hospital crisis. The lack of resources and of a long-term comprehensive and sustainable strategy puts intense pressure on Colombian medical staff and departmental health management, which do not have sufficient means to address the crisis in the Colombian health system, a system which was already in a run-down state.

According to the Colombian Ministry of Health of Colombia, a budget of almost COP3,000 million (more than US$1 million) is needed in 2018 to treat people living with HIV and a further COP12,200 million (approximately US$4 million) for comprehensive care to be provided to pregnant women with both high and low-risk pregnancies. Budgetary constraints mean that treatments for other chronic diseases cannot be considered guaranteed. Colombia, like Venezuela, has an obligation to accept international cooperation, if necessary.

Colombia has ratified the Convention 5 and Protocol relating to the status of refugees6, and also incorporates in its domestic legislation the definition of refugees set out in the Cartagena Declaration on refugees7. This Declaration broadens the traditional definition of a refugee – understood as someone who has fled their country for fear of persecution on the basis of race, religion, political opinion, nationality or social group – to encompass also those who have fled their country because their lives, security or freedom have been threatened by generalized violence, foreign aggression, internal conflicts, massive violation of human rights or other circumstances which have seriously disturbed public order8.

However, in spite of the fact that its domestic law also contains this expanded definition of refugee, and that it is a country with more than 340,000 refugees abroad9, the number of Venezuelans who have been granted refugee status in Colombia is very small10.

During the last five years, only 79811 Venezuelan citizens have applied for refugee status in Colombia and of these only 57 have been granted refugee status since 201312. In other words, Colombia has granted refugee status to an average of 11 Venezuelan citizens a year in the last five years, and it is believed that the number last year was even lower13.

The opening of a preliminary review on Venezuela by the International Criminal Court reinforces evidence that crimes under international law have been committed, as Amnesty International has previously reported on a number of occasions14. If anything characterizes a situation of massive human right violations, it is a serious negative impact not only on civil and political rights, but also on social and economic rights.

The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) has expressed concern on several occasions about the grave violations committed in Venezuela15, and criticized the Venezuelan government's refusal to accept that there is a humanitarian crisis in the country16. Likewise, UN special rapporteurs expressed concern in February 2018 about the chronic lack of medicines, high rates of malnutrition and an extreme poverty rate of over 50%17. The IACHR, through reports18, public statements19 and protection measures, has underscored the grave situation facing the country in terms of civil and political, but also social and economic rights. Recent precautionary measures issued by the Commission concerning the risk to the lives of people with chronic diseases in Venezuela are further proof of this20.

In Colombia, the asylum system, regulated by Decree 2840 (2013)21, incorporates not only the traditional definition of refugee, but also the extended definition contained in the Cartagena Declaration. The country's own internal regulations require Colombia to protect not only people such as political dissidents who are being persecuted in Venezuela, but also those whose lives are in grave danger because they do not have access to medicines to treat their illness or medical condition.

Amnesty International has documented the case of Daniel,* a Venezuelan living with HIV who obtained refugee status in Mexico in 2017 because of the risk posed to his life by not having anti-retroviral treatment in a context that the Mexican Committee for Refugee Assistance (Comisión Mexicana de Ayuda al Refugiado, COMAR)22 assessed as constituting massive violations. This shows that people with chronic diseases may warrant international protection23.

Roxana Chasoy Tandioy, is just six years old and from the Barinas State. She has steroid resistant nephritic syndrome, which can lead to irreversible kidney damage, requiring a transplant and dialysis. She was diagnosed in the Dr Luis Razetti de Barinas Hospital where doctors told her parents that there was nothing they could do to treat her oedematization (swelling) or to guarantee she would get the medicines she required. As she is resistant to steroids, she needs immunosuppressants and, depending on the assessment of her condition, she may require dialysis or even a transplant to save her life. Roxana's parents told Amnesty International that she is very depressed as she feels discriminated against because she has not had access to the treatment required on the grounds that she is not Colombian. Colombian legislation only guarantees treatment that falls within the emergency services to foreign nationals. Her family is hoping that the judicial protection process (tutela) will be resolved in their favour so that all her treatment is covered.

Cases of people like Roxana’s and those of other Venezuelan patients with chronic conditions living in Colombia should be evaluated on an individual basis by the Colombian state. If the circumstances warrant, given the current situation in Venezuela, they should be considered refugees in line with international and national protection standards and in accordance with what is set out in Colombia's own domestic regulations.

In addition, Colombia should ensure special medical care for pregnant or nursing women, in recognition of their special protection needs24. In order to do this, the Colombian authorities must put in place all the necessary measures to guarantee the right to health, both through existing resources within the state as well as those available from the international community through international cooperation and assistance25.